Learning in Healthcare Focuses on Helping Learners and Faculty Move Through and Understand the Stages of Competence.

West Haven, CT, June 29, 2016 (Newswire.com) - Although there are multiple (maybe hundreds) of competency models that exist, the basic principles are the same. Understanding where both the learner and the facilitator are in stages of competence can help improve the learning process. The difficulty comes when learning becomes tacit (i.e. gut feel/intuition based on principles or structures of mental models) versus explicit (i.e. skills, knowledge or surface features of mental models).

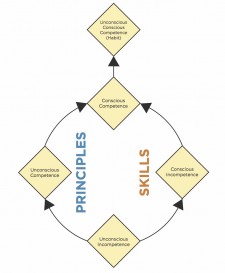

The model below is based upon principles authored by Dr. Stephen R. Covey (author of the 7 Habits of Highly Effective People):.

Learners can be unconsciously incompetent while their faculty are unconsciously competent, resulting in a complete block in understanding each other.

Jay Zigmont, Learning Innovator/Founder

Each time we start learning a concept, we are "unconsciously incompetent." In healthcare, this learner is the most dangerous to patient safety, as they ‘don't know what they don't know', and, therefore, may not know when to call for help. Learners in this first stage of competence need experiences in a safe learning environment (simulation fits well here) to move into conscious incompetence, which will allow them to learn.

Learners who are making the move from unconscious to conscious incompetence may find an experience difficult, as their confidence may suffer a blow by realizing they are incompetent at something. There is data suggesting when a learner realizes they are incompetent in one thing (e.g. electronic medical records or EMR), their clinical skills they are competent in can suffer (e.g. IV skills). Part of this may be explained by the ‘switching' between tacit (principle or structure based) thought and explicit knowledge.

When learners are coming out of unconscious incompetence, sometimes they just ‘get it' and can achieve the outcome or new behavior without truly understanding why (unconscious competence). In this case, they have acquired a principle or structure tacitly, but not explicitly. As the learner develops expertise, they may then move on to conscious competence (putting the tacit and explicit together), or may never get there.

Finally, as someone becomes an expert via experience, the learning becomes a habit, and they move into unconscious conscious competence. Unconscious conscious competence is a big way of saying that they have both the tacit and explicit knowledge, yet the entire thing has become tacit and challenging for the learner to explain. An excellent example of this was an ED nurse who explained to me that she could tell, with greater than ninety percent accuracy, if a patient is going to live or die in the ED by looking at their feet. She couldn't say exactly how or why that works, but it ‘just does.' After analyzing her habit, we found that in a major medical or trauma event there are multiple providers around the patient and often all the nurse can see is the patient's feet. What this nurse was cluing into were things like positioning/posture, color, texture, tone, etc., which are all signs of patient status, but tough (nearly impossible) to teach anyone.

The difficulty in facilitating learning is when the teacher is in unconscious conscious competence, and the learner is unconsciously incompetent. In this case, both the learner and facilitator may have trouble expressing themselves, and it may turn into a circular discussion (i.e. I don't know why it just is… vs. I don't understand what I am missing…). It may be easier for a new learner to learn from someone earlier in their career (ideally in conscious competence) even if that person is not an ‘expert' yet. Essentially, we can share our thoughts more easily with one level above or below us.

Educators often have difficulty with learners who ‘believe they know it all'. Students exhibiting a ‘false bravado' may be covering their conscious incompetence. Learners who feel the need to ‘cover' may not feel that it is a safe learning environment, which is the responsibility of both the learner and facilitator (and in some cases may be because of peer pressure). Luckily simulation is the great equalizer and will help peel away any false bravado.

If you are ‘forcing' someone out of their false bravado, or into conscious incompetence, be ready for an emotional response. Defusing becomes more important as they may lash out at the equipment (e.g. the manikin isn't real) or the teacher (i.e. you didn't tell me that). The learner may have displaced anger, and our job as a facilitator is to help them through to the next step in as comfortable a process as possible.

We need to work toward helping learners to understand that we all go through these stages of competence, and it is good to be aware of where you are. Our society has put so much pressure and emphasis on ‘grades' that learners may feel that being consciously incompetent is ‘failing,' and avoid it. Unfortunately, this feeling of failing may cheat the learner out of the learning. Thus the facilitator needs to be very aware of “where” the learner is in their learning process and their emotional milieu/makeup.

This part of a series called "Learning That Works" by Jay Zigmont, Ph.D., CHSE-A (jay.zigmont@gmail.com ). For a video on this topic and more information, visit http://L9.LearningInHealthcare.com . The principles above are part of the core content (Learning Card 9) of the Foundations of Experiential Learning Manual (available at http://FEL.learninginhealthcare.com ).

Source: Learning in Healthcare